February 6 - March 14, 2015

FALSE NATURE

Joshua Band

Curated by Cameron Brian and Ruth Santee

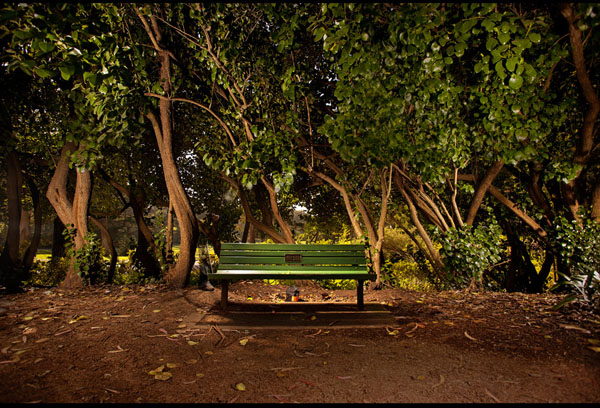

False Nature began as a photographic study of urban, night landscape and eerie natural daytime landscapes. This body of work explores the familiarity of liminal spaces, those empty places that all of us recognize but take little notice of. Using formal elements within the frame, artist Josh Band constructs a stage for a non-existent actor, one whose presence is desired. “I’m interested in finding the theater in unnameable, though familiar places” states Band. This project has evolved with the introduction of studio lighting to the daytime landscape, in effect, creating a question about time through the use of inexplicable, enigmatic light. Band explores the partnership between nature and the studio, “The Real” vs. that which is fabricated. Band realized that Golden Gate Park and most municipal, state, and national parks are completely fictional constructions, providing us a very directed experience about what we have come to believe and buy into as the "natural world."

“Upon realizing that the park was more like a Disney-like construction, I felt I had to explore further. I began to see the park, and other parks, and landscaping in general, as staged theatrical sets, dioramas constructed to provide us with the setting to perform, and take part in a directed and choreographed fictional experience of ‘nature’."

“Upon realizing that the park was more like a Disney-like construction, I felt I had to explore further. I began to see the park, and other parks, and landscaping in general, as staged theatrical sets, dioramas constructed to provide us with the setting to perform, and take part in a directed and choreographed fictional experience of ‘nature’."

Each image is available in the following sizes:

6" x 9", printed in a limited edition of 25

12" x 16", printed in a limited edition of 25

24" x 36", printed in a limited edition of 15

30" x 45", printed in a limited edition of 15

40" x 60", printed in a limited edition of 10

6" x 9", printed in a limited edition of 25

12" x 16", printed in a limited edition of 25

24" x 36", printed in a limited edition of 15

30" x 45", printed in a limited edition of 15

40" x 60", printed in a limited edition of 10

|

The Narrator, 2012

Archival Pigment Print Black Box, 2011

Archival Pigment Print Cove, 2012

Archival Pigment Print |

Proscenium, 2012

Archival Pigment Print Monologue, 2012

Archival Pigment Print Logline, 2012

Archival Pigment Print |

Act II, 2011

Archival Pigment Print Backdrop, 2011

Archival Pigment Print Counter, 2011

Archival Pigment Print |

Transmission Gallery co-director Ruth Santee's interview with artist Joshua Band.

Jan. 2015

TG: How long have you been working on this body of work?

JB: This body of work began in 2010 and I continue to evolve the formal production and post-production techniques involved in creating the False Nature photographs. I have worked both digitally, as used digital tools to create the body of work presented in this exhibition, and in an analog capacity. I am constantly exploring the concepts and ideas that are central and tangentially related to this project.

TG: When did you first start taking notice of “False Nature” ?

JB: I first became aware of "False Nature" when moving from Metro Detroit, Michigan to San Francisco, California. One day, I was walking around Golden Gate Park enjoying my escape from the loud and busy city. My experience involved aimlessly wandering down the many quiet and peaceful paths found in the park. I encountered chirping birds fluttering overhead, endless green and flowering plant life, many species I had never seen (and later found are not native to this area of the world) and quietly contemplated life. I enjoyed my escape and was casually interested in the park's history. so I decided to do a little research. I quickly realized that Golden Gate Park and most municipal, state, and national parks are completely fictional constructions, providing us a very directed experience about what we have come to believe and buy into as the "natural world." I found that the park relied on its army of gardeners, landscape designers and urban planners,and that without the regular bulldozing of sand dunes bordering the park back to the ocean (that would otherwise take over much of the park in a matter of days or weeks). I found that those rocks and boulders, that guided me along the various pathways through the park, were carefully sculpted out of composite materials (constructed on-site). Even the waterfalls are turned off in the evening. Without massive manpower and intervention ,including the carefully hidden maintenance of the park's "natural" facade, it would revert to a wild state that we would be barely recognizable as what we all know and love as Golden Gate Park. Upon realizing that the park was more like a Disney-like construction, I felt I had to explore further. I began to see the park, and other parks, and landscaping in general, as staged theatrical sets, dioramas constructed to provide us with the setting to perform, and take part in a directed and choreographed fictional experience of "nature."

TG: How quickly do you locate the desired shot for a photo? Do you know right away, or does it take time or even a return trip?

JB: I usually identify these places immediately and instinctively but I often do scout locations prior to shooting.There are a few key elements when scouting locations prior to hauling out all the studio lighting and equipment needed to produce the content for a single image. I look for places that feel "familiar" and are located along a path, or road, between destinations people frequent. I look for a location I can formally identify as a "stage," or a backdrop, sometimes relying on objects, such as trees, to bookend a "void," an empty placeholder for a missing subject, the actor. This "void" becomes a place of tension, a location where something mysterious will be enacted or where something has already happened.

TG: You seem to lean towards landscapes in your photography. What other subject matter interests you?

JB: I lean toward landscape in this body, and tangential bodies, of work, although, I have explored portraiture and still life quite a bit, both commercially and within the fine art domain. I like to claim that the False Nature project is environmental portraiture, where the viewer can't help but project him/herself onto the "stage" as the subject, like a mirror. Sometimes, I claim the False Nature project is still life, a man-made, constructed diorama where the park and our experience within is directed, and the plants and paths are merely prop objects to support the performance of "nature." I feel that categories like portraiture, landscape, and still life are meant to be manipulated, expanded, and as often as possible, broken.

TG: What kind of camera(s) to you use? Do you prefer digital to 35mm?

JB: I use a Canon 5D Mark II as my primary image capture device. I have experimented with large format film and other means of image capture but find the 35mm dSLR to be the most efficient way of capturing what I see for the purposes of constructing a familiar and believable, yet fictional place...

TG: Tell readers about your process, do you take photos everyday? Weekly? Monthly?

JB: All of my photography work within the past 5-6 years involves studio lighting, set construction, and quite a bit of planning. The pre-production spent creating a single image may take hours, or even days, involving location scouting, meticulously diagramming my lighting plans, and often involving the assembly of a support team of production assistants to help execute shoot production.

I make use of many commercial film and photo production techniques and methodologies. The content needed for a single final image may take up to four hours to create in the field. It involves setting up and tearing down studio equipment, waiting for the ambient light and other environmental factors to be just right, and as my images are void of any representations of people, I have to wait for the right moments, in sometimes very busy locations.

After acquiring all the image content, there's significant post-production involved in compositing, construction and editing my final image. I feel that this is where the real magic happens and where I can present an impossible, yet believable reality. This involves having to carefully plan and architect the images from pre-production, through production, onto post-production.

I very much enjoyed taking photos every day, in the past, always with a camera hanging over my shoulder. When I came to San Francisco to pursue my graduate degree at the San Francisco Art Institute, I enjoyed diving deeply into critical art theory and art history and became very used to photographing in a much more intentional and structured way, partially due to the need to plan out my work in advance and that most of my imagery rely on heavy manipulation and construction. I now miss my more casual, daily relationship with photography. Some of my best work has been the casual, immediate, shot-from-the-hip "snapshot." I realize now that school, and the structures it provided, were both constructive in helping me focus my ideas and work, but I also see that it has limited my ability to simply enjoy exploring photography in a casual day-to-day way. I intend to correct this and see both my camera phone and the dSLR as tools to me help re-discover the daily pleasures that come from shooting with no expectations and purely for the sake of having fun.

TG: As a photographer/artist, do you think colleges should continue to offer traditional classes in “wet” black and white photography? Or has the digital camera completely replaced it?

JB: I believe colleges should absolutely offer "wet" black and white photography classes. My personal practice is completely digitally oriented, however. I coordinate SFAI's darkrooms and support photography students throughout the school. SFAI has an important place in history when it comes to photography's transition into the world of fine art. Ansel Adams, Minor White, Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston, and Dorothea Lange, to name a few, launched the first collegiate fine art photography program in the country. Maintaining and respecting tradition, including introducing students to analog photography and other historical analog photographic processes, is a huge part of SFAI's legacy.

Working with film in the field and having to wait to develop it to access the photograph, slows a beginning student artist down, and in doing so, often causes one to think more carefully and intentionally about the technical, aesthetic, and conceptual while working. Film also allows for some amazingly magical surprises, something that I believe is often the key that transforms a student's budding interest in photography into a life passion. Analog provides us a place detached from reality, a place to dream, imagine and express. Analog is often imperfect, grainy and lacking sharpness. Analog provides us the ability to see, interpret and represent the world in a way that is unlike the perfectly clean and crisp, predictable, and sometimes overly descriptive color imagery created, at least in a default mode, by a digital camera. Digital cameras offer immediacy, so in that sensem it is a helpful learning tool to learn the basics. Black and white photography is commonly used as an introduction to new students as it simplifies discerning and understand form, content, how light operates, and the mechanics of the camera. Often, jumping right into the digital imaging world, students fly by these key learning goals.

The darkroom is a completely different experience in image making when compared to the "digital darkroom" space ruled by Photoshop. The "wet" darkroom is tactile and sensory, it is much more about direct technical crafting, chemical and media experimentation, and is usually far less involved in producing overwhelming mountains of imagery. The analog process allows the new student to make and experiment, whereas the ease and immediacy of the digital world often leads to consuming the world in massive quantity quickly, documenting every experience, every moment, no matter how trivial. The speed, immediacy, ease, and quantity often involved in the digital image making process sometimes causes us to forget why we picked up the camera in the first place. That said, the digital world and the hybrid analog-digital world are often areas that intermediate and advanced photography students decide to explore, once a foundation has been built. Students should be learning as many photographic tools as possible during the scholastic experience, both analog and digital.

TG: What advice do you have for aspiring photographers?

JB: Experiment, explore, share your images with the world. I, and, I'm sure many others would love to see how you see, and photography is a wonderful tool to help us communicate, share, and express our experiences and feelings about our lives and the world around us.

Jan. 2015

TG: How long have you been working on this body of work?

JB: This body of work began in 2010 and I continue to evolve the formal production and post-production techniques involved in creating the False Nature photographs. I have worked both digitally, as used digital tools to create the body of work presented in this exhibition, and in an analog capacity. I am constantly exploring the concepts and ideas that are central and tangentially related to this project.

TG: When did you first start taking notice of “False Nature” ?

JB: I first became aware of "False Nature" when moving from Metro Detroit, Michigan to San Francisco, California. One day, I was walking around Golden Gate Park enjoying my escape from the loud and busy city. My experience involved aimlessly wandering down the many quiet and peaceful paths found in the park. I encountered chirping birds fluttering overhead, endless green and flowering plant life, many species I had never seen (and later found are not native to this area of the world) and quietly contemplated life. I enjoyed my escape and was casually interested in the park's history. so I decided to do a little research. I quickly realized that Golden Gate Park and most municipal, state, and national parks are completely fictional constructions, providing us a very directed experience about what we have come to believe and buy into as the "natural world." I found that the park relied on its army of gardeners, landscape designers and urban planners,and that without the regular bulldozing of sand dunes bordering the park back to the ocean (that would otherwise take over much of the park in a matter of days or weeks). I found that those rocks and boulders, that guided me along the various pathways through the park, were carefully sculpted out of composite materials (constructed on-site). Even the waterfalls are turned off in the evening. Without massive manpower and intervention ,including the carefully hidden maintenance of the park's "natural" facade, it would revert to a wild state that we would be barely recognizable as what we all know and love as Golden Gate Park. Upon realizing that the park was more like a Disney-like construction, I felt I had to explore further. I began to see the park, and other parks, and landscaping in general, as staged theatrical sets, dioramas constructed to provide us with the setting to perform, and take part in a directed and choreographed fictional experience of "nature."

TG: How quickly do you locate the desired shot for a photo? Do you know right away, or does it take time or even a return trip?

JB: I usually identify these places immediately and instinctively but I often do scout locations prior to shooting.There are a few key elements when scouting locations prior to hauling out all the studio lighting and equipment needed to produce the content for a single image. I look for places that feel "familiar" and are located along a path, or road, between destinations people frequent. I look for a location I can formally identify as a "stage," or a backdrop, sometimes relying on objects, such as trees, to bookend a "void," an empty placeholder for a missing subject, the actor. This "void" becomes a place of tension, a location where something mysterious will be enacted or where something has already happened.

TG: You seem to lean towards landscapes in your photography. What other subject matter interests you?

JB: I lean toward landscape in this body, and tangential bodies, of work, although, I have explored portraiture and still life quite a bit, both commercially and within the fine art domain. I like to claim that the False Nature project is environmental portraiture, where the viewer can't help but project him/herself onto the "stage" as the subject, like a mirror. Sometimes, I claim the False Nature project is still life, a man-made, constructed diorama where the park and our experience within is directed, and the plants and paths are merely prop objects to support the performance of "nature." I feel that categories like portraiture, landscape, and still life are meant to be manipulated, expanded, and as often as possible, broken.

TG: What kind of camera(s) to you use? Do you prefer digital to 35mm?

JB: I use a Canon 5D Mark II as my primary image capture device. I have experimented with large format film and other means of image capture but find the 35mm dSLR to be the most efficient way of capturing what I see for the purposes of constructing a familiar and believable, yet fictional place...

TG: Tell readers about your process, do you take photos everyday? Weekly? Monthly?

JB: All of my photography work within the past 5-6 years involves studio lighting, set construction, and quite a bit of planning. The pre-production spent creating a single image may take hours, or even days, involving location scouting, meticulously diagramming my lighting plans, and often involving the assembly of a support team of production assistants to help execute shoot production.

I make use of many commercial film and photo production techniques and methodologies. The content needed for a single final image may take up to four hours to create in the field. It involves setting up and tearing down studio equipment, waiting for the ambient light and other environmental factors to be just right, and as my images are void of any representations of people, I have to wait for the right moments, in sometimes very busy locations.

After acquiring all the image content, there's significant post-production involved in compositing, construction and editing my final image. I feel that this is where the real magic happens and where I can present an impossible, yet believable reality. This involves having to carefully plan and architect the images from pre-production, through production, onto post-production.

I very much enjoyed taking photos every day, in the past, always with a camera hanging over my shoulder. When I came to San Francisco to pursue my graduate degree at the San Francisco Art Institute, I enjoyed diving deeply into critical art theory and art history and became very used to photographing in a much more intentional and structured way, partially due to the need to plan out my work in advance and that most of my imagery rely on heavy manipulation and construction. I now miss my more casual, daily relationship with photography. Some of my best work has been the casual, immediate, shot-from-the-hip "snapshot." I realize now that school, and the structures it provided, were both constructive in helping me focus my ideas and work, but I also see that it has limited my ability to simply enjoy exploring photography in a casual day-to-day way. I intend to correct this and see both my camera phone and the dSLR as tools to me help re-discover the daily pleasures that come from shooting with no expectations and purely for the sake of having fun.

TG: As a photographer/artist, do you think colleges should continue to offer traditional classes in “wet” black and white photography? Or has the digital camera completely replaced it?

JB: I believe colleges should absolutely offer "wet" black and white photography classes. My personal practice is completely digitally oriented, however. I coordinate SFAI's darkrooms and support photography students throughout the school. SFAI has an important place in history when it comes to photography's transition into the world of fine art. Ansel Adams, Minor White, Imogen Cunningham, Edward Weston, and Dorothea Lange, to name a few, launched the first collegiate fine art photography program in the country. Maintaining and respecting tradition, including introducing students to analog photography and other historical analog photographic processes, is a huge part of SFAI's legacy.

Working with film in the field and having to wait to develop it to access the photograph, slows a beginning student artist down, and in doing so, often causes one to think more carefully and intentionally about the technical, aesthetic, and conceptual while working. Film also allows for some amazingly magical surprises, something that I believe is often the key that transforms a student's budding interest in photography into a life passion. Analog provides us a place detached from reality, a place to dream, imagine and express. Analog is often imperfect, grainy and lacking sharpness. Analog provides us the ability to see, interpret and represent the world in a way that is unlike the perfectly clean and crisp, predictable, and sometimes overly descriptive color imagery created, at least in a default mode, by a digital camera. Digital cameras offer immediacy, so in that sensem it is a helpful learning tool to learn the basics. Black and white photography is commonly used as an introduction to new students as it simplifies discerning and understand form, content, how light operates, and the mechanics of the camera. Often, jumping right into the digital imaging world, students fly by these key learning goals.

The darkroom is a completely different experience in image making when compared to the "digital darkroom" space ruled by Photoshop. The "wet" darkroom is tactile and sensory, it is much more about direct technical crafting, chemical and media experimentation, and is usually far less involved in producing overwhelming mountains of imagery. The analog process allows the new student to make and experiment, whereas the ease and immediacy of the digital world often leads to consuming the world in massive quantity quickly, documenting every experience, every moment, no matter how trivial. The speed, immediacy, ease, and quantity often involved in the digital image making process sometimes causes us to forget why we picked up the camera in the first place. That said, the digital world and the hybrid analog-digital world are often areas that intermediate and advanced photography students decide to explore, once a foundation has been built. Students should be learning as many photographic tools as possible during the scholastic experience, both analog and digital.

TG: What advice do you have for aspiring photographers?

JB: Experiment, explore, share your images with the world. I, and, I'm sure many others would love to see how you see, and photography is a wonderful tool to help us communicate, share, and express our experiences and feelings about our lives and the world around us.